I remember so many children who have taken their lives – it is a national abomination

Gerry Georgatos

4 Feb 2019

The disproportionate suicide toll of Indigenous Australians is a humanitarian crisis that cannot be allowed to continue.

I remember a father who found his son hours after his suicide. The father lay his son down and cradled his body through the night until responders arrived in the morning.

I remember the distraught family of a young man who only a week before his suicide had run into a burning house and rescued a young mother and her baby. I remember attending the funerals of three young people in the one community – three burials in five days, three graves in a row.

The youngest was a 15-year-old girl.

I wailed on the inside as I stared at the graves. Weeks later the loss of two more young people would make it five graves in a row of youth unlived.

I remember a father of six children who took his life, a mother of five children who took her life, a pregnant mother who took her life. I remember a nine-year-old child who took his life, a 10-year-old child who took her life, an 11-year-old boy who took his life, a 12-year-old girl who took her life.

Hauntingly etched in my mind’s eye are three children – aged six, eight and 10 years – together attempting suicide from a tree, saved by older children.

You ask, how can it be imaginable for a six-year-old to attempt the ending of their life? They were all of First Nations heritage. With the exception of only one, they lived below the poverty line and the majority in “crushing” poverty.

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander suicides comprise 6% of Australia’s total suicides but, shockingly, 80% of child suicides aged 12 and below are of Aboriginal children.

For the past decade, nearly 30% of the child suicides to age 17 were comprised of Aboriginal children. In the past year I estimate this harrowing crisis has increased to 40%. In the first nine days of the new year, five First Nations girls, two of them aged 12 years, lost their lives to suicide.

As I write this there have been three more First Nations children who have been lost and two more, including an 11-year-old, who are fighting for life and, if they survive, will never again be the same.

I have often said “the nation should weep” at this harrowing tragedy, which is more than just a national shame – a national disgrace, an abomination, a damning condemnation of who we remain as a nation.

Each year, I support hundreds of suicide-affected families, hundreds of individuals who have attempted suicide or who are at risk – from migrant-born Australians, young and older Australians, who lived affluent or homeless. But the disproportionate suicide toll on First Nations Australians is a humanitarian crisis that cannot be allowed to continue its now uninterrupted three decades long tragedy.

One in 17 of all First Nations people’s deaths is a suicide, while half of all First Nations youth deaths aged 17 years and younger is a suicide.

Discriminatory crushing poverty is the catastrophic narrative resulting in an arc of pronounced negative issues culminating in diabolical numbers of First Nations youth and older who are incarcerated, self-harming and killing themselves. The suicide rate of First Nations Australians is two-and-a-half times that of the national population.

In Australian 14% live below the poverty line but 40% of First Nations Australians live below the poverty line – that’s also a two-and-a-half times differential – an absolute correlation. In my research, experiential and otherwise, nearly 100% of the suicides of First Nations peoples are of individuals who lived below the poverty line, the highest proportion in a crushing poverty, the type not experienced by other Australians living below the poverty line.

The suicide rate of First Nations Australians who live above the poverty line is very low and much less than the suicide rate of the rest of Australians living above the poverty line.

Our focus needs to be on lifting people out of poverty and in doing away with the discriminatory crushing poverty that should have no place in the world’s 12th biggest economy.

I have travelled hundreds of First Nations homelands and communities and a significant proportion are hovels of human misery, corrals of degradation. They are not of the making of the people living in them but of neglect and deprivations made by one government after another.

In remote living communities, eight out of every 10 children will never finish school, with half not completing primary school. These are infrastructure starved communities without hope on the horizon.

Individuated resilience and other psycho-educative strength training, unless coupled with access to opportunities including education and employment, cannot alone score someone to a psychosocial positive self. How far and for how long can someone adjust their behaviour without access to meaningful hope on the horizon?

It is a reprehensible myth that governments have prioritised the catastrophic suicide crises of the nation’s most suicide affected.

The Council of Australian Governments must prioritise equality and universal rudimentary rights. The suicide rate will be reduced between First Nations peoples and the rest of Australia when the poverty rates are reduced.

There must be psychosocial support to help people improve their life circumstances, to reduce disordered thinking, to reduce the sense of helplessness. There must be remunerated community buy-in, whether in the remote or in the cities; workforces of mentors – skilled up – who can be guiding lights, shoulders to rest on, for the vulnerable, for exhausted families reaching out for help for a struggling loved one.

The death of a child is always heartbreaking and when it is by suicide it as devastating as it gets. Unless governments heed and focus, more children than ever before will be lost. They must prioritise those most in need, those whom for too long our governments have been leaving behind to languish impoverished, in shanties without white goods, without secondary schools, without recreational facilities.

Like migrant-born children who fled to Australia from oppressive socioeconomic disadvantages, First Nations youth that go to university are among the most likely, most driven to succeed. We must do everything that we can to lift sisters and brothers to an improved life circumstance, to various opportunity and they will do the rest.

The more education someone has completed, the greater their protective factors to steering clear from suicidal ideation. The majority of the national prison population has not completed year 12 – in fact, the majority has not completed year 9.

High levels of education are a more significant protective factor than fulltime employment. More education translates to a dawn of new meanings, to a better understanding of the self, to a more positive psychosocial self, to the pursuit of what happiness and its contexts can and should mean.

The majority of First Nations families who have lost a loved one to suicide have lost another loved one and another.

I remember a 10-year-old child lost to suicide. The year before she found her 11-year-old first cousin had taken their life. Two years earlier her 13-year-old sister had taken her life.

They lived in crushing poverty and in an arc of distressing issues borne of inescapable poverty. In the past few years, of the hundreds of First Nations suicide affected families I have responded to, nearly all were encumbered by abominable levels of poverty.

• Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher. He is also the national coordinator of the National Indigenous Critical Response Service and of the National Child Sexual Abuse Trauma Recovery Project.

• Crisis support services can be reached 24 hours a day: Lifeline 13 11 14; Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467; Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800; MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78; Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636.

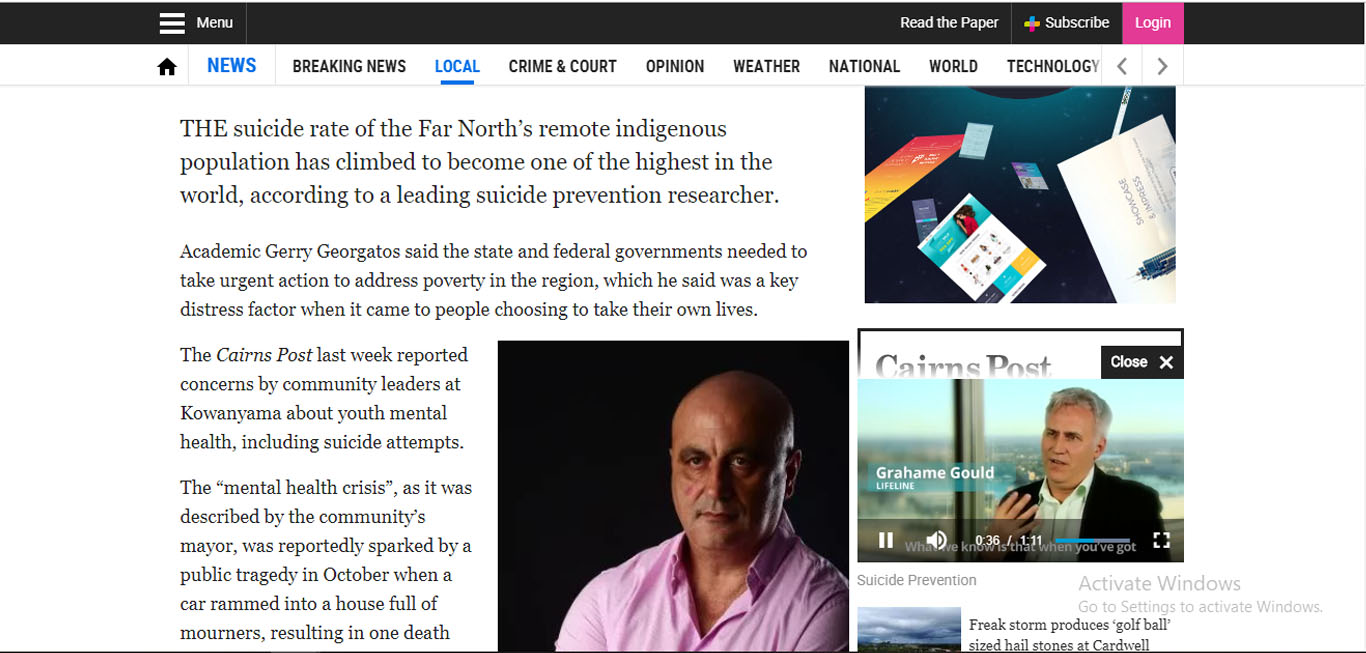

Alarming suicide rate at Kowanyama needs to be addressed, says academic

JIM CAMPBELL, The Cairns Post

July 3, 2017

THE suicide rate of the Far North’s remote indigenous population has climbed to become one of the highest in the world, according to a leading suicide prevention researcher.

Academic Gerry Georgatos said the state and federal governments needed to take urgent action to address poverty in the region, which he said was a key distress factor when it came to people choosing to take their own lives.

The Cairns Post last week reported concerns by community leaders at Kowanyama about youth mental health, including suicide attempts.

The “mental health crisis”, as it was described by the community’s mayor, was reportedly sparked by a public tragedy in October when a car rammed into a house full of mourners, resulting in one death and 25 people being seriously injured.

Kowanyama Aboriginal Shire Council Mayor Michael Yam pleaded for government help to address the situation, highlighted with the suicide of a 23-year-old man last month.

Mr Georgatos warned the crisis would only worsen if distress factors such as homelessness and unemployment were not tackled.

“The narrative is poverty and that’s what needs to be addressed,” he said.

Mr Georgatos said between 2001 and 2012 there were 60 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suicides in Cape York.

He said there had been 40 since 2012.

Cape health boss welcomes review into town’s ‘mental health crisis’

“Those numbers are incredibly high for the size of the population in the region,” he said.

“And it’s an accepted fact that for every suicide, for every loss, there could be anywhere between 10 and 20 attempted suicides.”

Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service last week flew an experienced social worker into the town following the mayor’s plea for help.

The social worker is in addition to a mental health clinical nurse consultant who travels to Kowanyama weekly for four-day visits.

But Mr Georgatos said Kowanyama needed permanent, live-in counsellors — male and female — to build relationships and offer crisis counselling where and when it was needed.

Health care provider Apunipima Cape York Health Council chief executive Cleveland Fagan also said his team was working on solutions to take to the council to address the issues identified by the mayor.

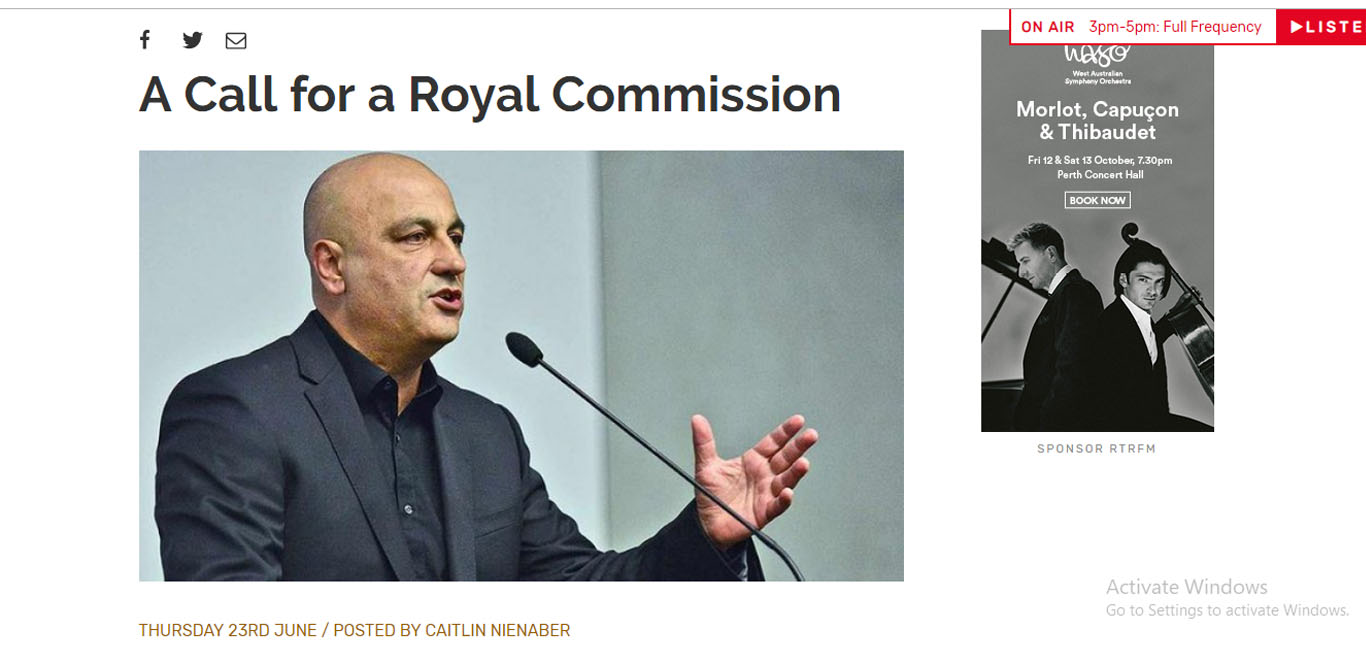

Migrant suicide is lost in translation

"Support can make a difference", says suicide prevention expert Gerry Georgatos

29 April 2016 1:42pm

The statistics are harrowing: more than one in four of Australia’s suicides are of people born overseas. The Australian Bureau of Statistics recorded nearly 3,000 cases of suicide in 2014, an increase of around 300 on the preceding annual toll. Among them around 800 are of migrants. According to the ABS, the rates are higher among Australian residents born in New Zealand, as well as among females coming from Eastern Europe.

“Many migrants face xenophobia, misoxeny and relentless racism. It varies depending on the migrant group, ” says Gerry Georgatos, offering valuable insight. The activist and suicide prevention researcher, who works for the Institute of Social Justice and Human Rights, issued a statement, addressing the matter and calling for action: “The high suicide rates of many migrant cultures are lost and little is done to respond the unique needs in suicide prevention for Australians who were born overseas, for newly arrived migrants, for the children of migrants”, he says.

Georgatos warned that collectivised medians, a focus on overall national averages risks masking a true picture of migrant groups with elevated risks.

“We need more data disaggregation in order to ensure tailored support and awareness-raising. If we do not disaggregate we risk discrimination, we risk making people invisible, elevated risk groups become invisible. We must not leave anyone behind. The disaggregation will allow us to reach those most vulnerable with tailored support”, he adds.

Georgatos said that the underlying factors spiking high rates of mental health issues, depression and suicidal ideation vary from one migrant group to another. “There are myriad hurdles and barriers for some migrant groups in the first few years in Australia as opposed to other migrant groups. Some migrant groups are isolated even within a multicultural urban mass. Their self-worth, self-esteem and sense of being is corralled by the sense of isolation; some feel a sense of hopelessness soon after their arrival. Then there is fundamental among many migrant groups of the excessive burden to deliver on expectations, and many feel a sense of exhaustion, others a sense of failure. The pressures are psychosocially and pyschologically significant and impact the family dynamic, the children. Many of the children of migrants are also levied a suite of expectations, pressure to succeed at levels that across the board non-migrant children do not endure. The quotient of happiness becomes secondary or is distorted and bent into an intertwining with educational, career and material outcomes, expectations.”

“Migrating to a new country can be acutely traumatic, for many it can be chronically traumatic, and the situational trauma of relocation needs tailored support and this can only be delivered on the back of awareness raising of the issues. Through awareness raising new meanings dawn, there is an improved contextualising of the evaluation of life experiences. We must do everything possible to ensure that situational trauma does not degenerate into a constancy of traumas – multiple, composite – and as we know for many becomes aggressive complex trauma.”

Georgatos also warns that we must disaggregate not only to country of origin but to the means of migration and therefore include refugees who he believes have even more elevated risks to depression and suicidal ideation because “of the damaging experience they endured in immigration detention, some for years.”

“Furthermore, racism needs to be better understood by everyone – by its victims and by the perpetrators. Racism gets discussed at the surface level but a deep examination is yet to be had. We have soaked up the racism, the prejudices and misoxeny of the Cronulla riots, we continue to soak up the hatefulness of Islamophobia, the hate of the cultural norms of others, of perceptions of how different peoples appear. Having to soak up all this and then be expected to internalise the silences is toxic and this not only fractures society but dangerously isolates people.”

“One in three of Australia’s homeless are people who have been born overseas. If we want a future where we leave no-one behind we need more research and public discussions about the now, so we do not create for generations unborn underclasses of marginalised migrants or of their children coupled with multiple traumas, psychological damage.”

In Australia, suicide is the leading cause of death for males and females aged between 15 years and 45 years and the need for a comprehensive system of support and prevention is crucial. Gerry Georgatos is emphatic about the difference support can make: “People need people”, he says. “We must never allow any cultural group to become invisible”.