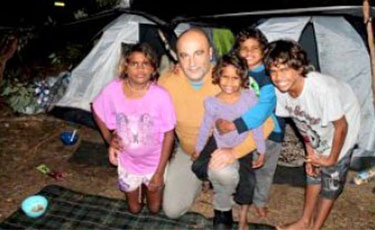

The plight of six children living in a tent on the outskirts of Perth has prompted a human rights group to call for a better system of prioritising families in need of public housing.

Spokesman for the Human Rights Alliance Gerry Georgatos said the family moved from a remote community in the Northern Territory to access better education opportunities for the children, who are aged from four to 16, before Christmas.

Mr Georgatos told 720 ABC Perth they approached government agencies for assistance, but the family may face a cold, wet winter in tents.

“They’ve been here for about five months, they’d hoped to have set themself up in some sort of accommodation, went to every agency and weren’t able to be supported into state housing,” he said.

“The waiting lists for which they’ve been prioritised for are, unbelievably, five years long.

“What we have is a four-year-old, a six-year-old, an eight, and 10, and 12, and 16 year olds, with the dad and the grandma living off a major highway in the outskirts of Perth in the bush, and having lived liked this for five, six months.”

Mr Georgatos said despite their housing situation, all of the children have been attending school regularly and were getting very good support from their school communities.

The grandmother is also serving on one of the schools’ parents and friends groups, and the children are involved in after school activities and sport.

Families with young children should get priority: Georgatos

Mr Georgatos said he knew of other families living in similar situations, and the Department of Housing needed a better system of priority for families in need.

“The Department of Housing are probably doing everything they can and behind the scenes even more so, but I think what we need is a triage approach to try and house some of these families with very young children, and just move them up the line and that’s just something that’s got to be done,” he said.

Spokesman for the Department of Housing Steve Parry said the waiting list for state housing was currently 20,294 – which represented about 43,000 people.

“We’re honest with our clients, we say, you’re not going to get a house next week or next month, we operate a wait-list which is date ordered, basically first-come, first-served,” he said.

“But within that we have a priority list which assesses people that need urgent accommodation.”

Mr Parry said there were 2,900 applicants on the “priority list” and they could be waiting up to six months for a home.

He said housing for larger families was more difficult as there were a limited number of larger properties.

A family with six children living in a tent on the outskirts of Perth will move into interim accommodation today after publicity about their plight led to numerous private offers of help.

Spokesman for the Human Rights Alliance, Gerry Georgatos, told 720 ABC Perth that the family had accepted a private offer of housing close to the children’s school.

“They will be having their first hot shower tonight after five months of homelessness,” Mr Georgatos said.

The family had spent five months living in a tent in Perth’s northern outskirts after they moved from a remote community in the Northern Territory before Christmas. The family moved to WA to access better education opportunities for the children, who are aged from four to 16.

Mr Georgatos said despite their housing situation, all of the children have been attending school regularly and were getting very good support from their school communities.

The family had approached government agencies for assistance but were placed on a state housing waiting list with a five year waiting period.

Since the media coverage, Mr Georgatos said “there has been a huge response from the public in terms of supplies, care packages, clothes and furniture”.

“I had about 20 offers of accommodation but we wanted to find accommodation close to the schools the kids are established at.

“Someone in the northern suburbs has put up their hand to take them in until we can secure permanent accommodation through whatever agency we can.”

Gerry Georgatos reveals the unemployment and homeless rates in Australia that we're not being told.

AUSTRALIA IS FACING homelessness and poverty levels the likes it has never known — nor that it’s prepared to admit.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), there are more than 116,000 homeless Australians.

At least, that’s how many they’ve identified.

However, the number is closer to 300,000 homeless Australians, with more than 100,000 of them being children. Since the data released from the ABS in 2011, we’ve identified that nearly one in five of Australia’s homeless are children aged 12 years and less.

Most Australians would not realise that there are currently thousands of children aged 12 years and less on our streets exposed to various violence and sexual predation.

Our governments, various institutions, funded organisations and bean counting statisticians need to scrub up and start telling the truth about the extensiveness of poverty – particularly of extreme poverty – and homelessness. I will not go down the path of why poverty and homelessness are under-reported but suffice to suggest that it is playing with people’s lives.

Australia is a relatively affluent nation, the world’s 13th largest economy with among the world’s highest median wages, but it is also home to extreme poverty, some of it akin to what we find in developing nations. Australia is hiding its growing poverty crisis that – within a couple of decades – I believe may directly affect one in two Australians.

We are told there are approximately 720,000 jobless Australians — but I argue there are more than two million jobless Australians.

We are told that 13.3% of Australians live below the poverty line. If the Henderson Poverty Line was reassessed, as I believe it should, 35% of Australians would be recorded as living in poverty.

We are told that 730,000 children live in poverty but I argue that more than two million Australian children live poor.

We are told that 116,000 Australians are homeless when it’s actually 300,000.

I have written voluminously on the ways forward, but here I will highlight only the fact that the Australian nation, in general, is not being told the truth of the extensiveness of its poor and homeless. Poverty, unemployment, homelessness are pronounced in the suicide toll. The poor, unemployed, homeless fill the prisons.

In my research, I have found that nearly half the prison population prior to arrest were homeless, more than two-thirds prior to arrest were not employed and nearly 90% of the national prison population has not completed Year 12.

I’ll call out the Federal Government data as false. We are being lied to.

Data is produced from premises. For instance, not all the unemployed are being counted. To be counted as unemployed you have to be registered with Centrelink and follow their rules in terms of looking for work.

If you work one hour per week, you are reported as employed.

I argue that there are at least six million Australians living in poverty but we are told that under three million Australians live below the poverty line.

Relative poverty is a measure contextualising annual income to cost of living demands and therefore has to do with low-income levels and the accumulation of cost of living stressors.

Absolute poverty describes individuals and families that are not able to provide basic necessities such as housing, food and clothing.

Classism will become this nation’s most hurtful sore and, though it will intertwine, it will subsume all the other “isms”. Poverty is mounting and, as a catastrophic crisis-in-waiting, it will tear at this nation.

Australia’s pensioners will comprise a significant proportion of Australian poverty. Today, a pension averages annually about $22,000. It’s already tough going if that is all one has. Poverty is the biggest issue.

I believe that the pension is trending to be worth the equivalent of $70 in present value in just 20 years time. That means the pension alone will mean dirt-poor living. Unless Australians have their home paid off by their retirement and $1 million saved in superannuation, they will live their last stretch of life in poverty.

Australia provides more than 400,000 social houses while around 170,000 families remain on the waiting lists. If social housing were to disappear, there would be millions more homeless Australians. In the decades ahead, millions more of such dwellings will be needed — but there is nothing to indicate that they will appear.

Future governments will resort to the worst types of tenements and to poverty-only precincts. That’s guaranteed because present governments – federal, state, local – do just about jack to respond to homelessness and to address poverty.

I also argue that the national unemployment rate is not 5.5% but that it is above 20%, maybe even 35%, of working Australians. 10% of Australia’s labour force is acutely underemployed and more than 1.1 million underemployed Australians are looking to work more hours per week.

The Northern Territory’s homelessness rates are the worst in the nation and are at the higher end of the homelessness scales on the global spectrum. According to the ABS in 2012, 734 in every 10,000 Territorians are homeless. This is more than 7% of the Territory’s people living homeless.

Outside of natural disasters and civil strife, that’s one of the world’s highest homelessness rates. When we disaggregate we find that the 7% translates to 12% of the Territory’s Indigenous Australians living homeless.

Sadly, the Kimberley region describes a similar tale, where 638 per 10,000 of the population are homeless. But, once again, as the homeless population majorly comprises of Indigenous Australians, one in eight of the Kimberley’s Indigenous Australians are homeless.

The Northern Territory has a homelessness rate 14 times the national average. There are regions of the Territory where the homeless comprise 15 to 30% of the local population. The East Arnhem has the highest homelessness rate at 28%.

Racism, call it institutional or structural, has disgraced this nation to the point of not lifting a finger to help our homeless and poverty affected brothers and sisters. But the future speaks of a time more torrid where this type of mass poverty will be experienced by millions of Australians. Classism will rear its ugly presence and become the new norm.

Imagine an Australia where 10% of its people are homeless, where a quarter of Australians live in extreme poverty and where between half to three-quarters of the Australian population live below the poverty line. It is coming.

Let’s start with the truth: the real story – presently – is 300,000 homeless Australians, more than 100,000 homeless children, 25% Australians of working age who are unemployed and millions of Australians living in poverty.

Mr Georgatos said despite their housing situation, all of the children have been attending school regularly and were getting very good support from their school communities.

The family had approached government agencies for assistance but were placed on a state housing waiting list with a five year waiting period.

Since the media coverage, Mr Georgatos said “there has been a huge response from the public in terms of supplies, care packages, clothes and furniture”.

“I had about 20 offers of accommodation but we wanted to find accommodation close to the schools the kids are established at.

“Someone in the northern suburbs has put up their hand to take them in until we can secure permanent accommodation through whatever agency we can.”