Ode to Ms Dhu a powerful means to expose racism and demand justice

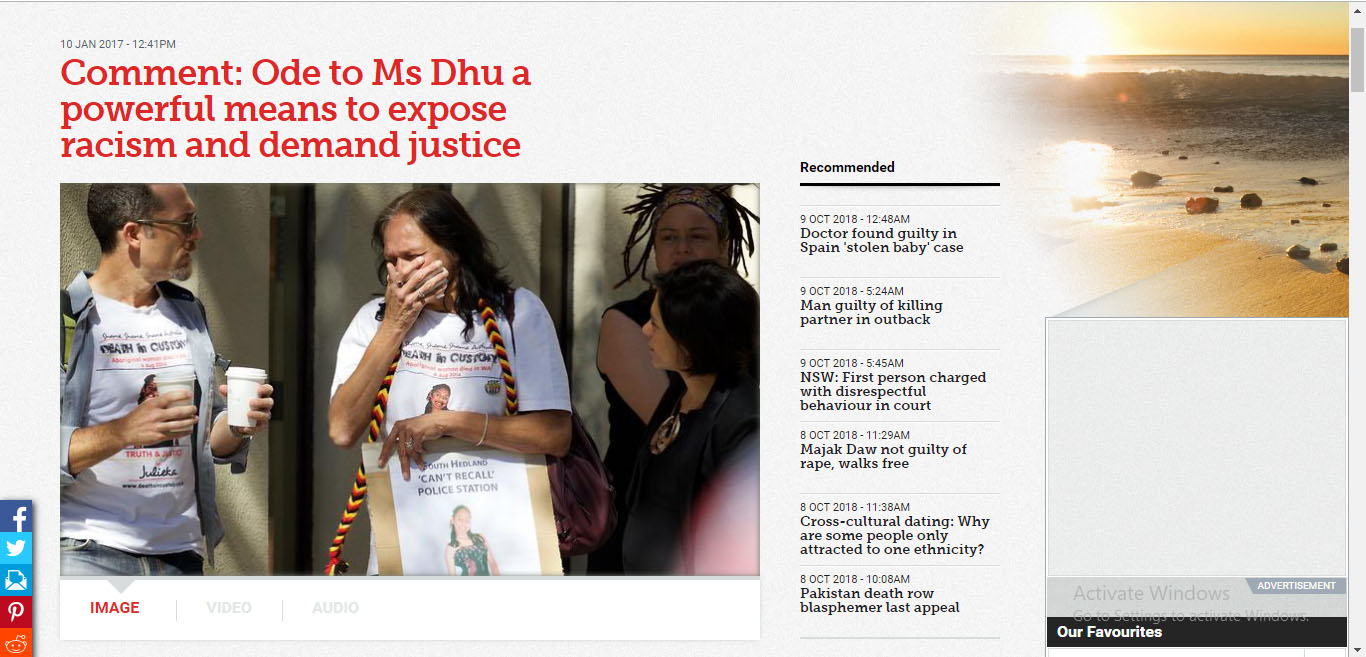

The Cat Empire’s Felix Riebl has just released a song about Ms Dhu’s death to create awareness, expose racism and demand for justice.

On August 4, 2014, I was phoned by Ms Dhu’s family. Only hours before the phone call, she had passed away at the hand of racism. Some will argue racism did not kill Ms Dhu, but I am of the view racism did.

Mainstream Australia only became truly aware of Ms Dhu’s death on December 16, when the CCTV footage of Ms Dhu’s final moments was finally released publicly, after a lengthy legal battle. Ms Dhu’s family wanted the footage to be shown for the benefit of the public interest.

When handing out her findings into the causes of Ms Dhu’s death, the West Australian coroner found Ms Dhu’s death was preventable, and police were ‘unprofessional and inhumane’.

As the CCTV footage lays witness, Ms Dhu was dragged, carted, and hauled to the pod of a police vehicle, as her spirit left behind her mortal coil. The footage is disturbing.

Some would say Ms Dhu was dumped into the paddy wagon ‘like a dead kangaroo’.

The rawness of this visual analogy was not lost on The Cat Empire’s Felix Riebl, who has just released a song about the events.

The renowned singer/songwriter had been reading my articles on Ms Dhu’s death and had contacted me to find out more.

Felix wanted to do something to raise awareness on Ms Dhu’s needless death. He felt the nation had to know about her abhorrent treatment in custody, and believes people should demand change.

Mid-last year, Felix emailed me a draft song: an ode in memory of Ms Dhu; a call to the nation’s principled and compassionate people to come as one and plea for justice.

When many rise, change happens

The song is a journey into injustice. It enumerates the wrongs Ms Dhu suffered in her last 48 hours.

Teenage female Aboriginal and Torres Strait youth choir, Marliya (Yindjibarndi for bush honey) from far north Queensland partnered with Felix.

Felix and Marilya capture the veils and layers of institutionalized systematic racism when they sing:

“…they carried her ‘like a dead kangaroo’, from her cell back to the same hospital who’d assumed that her pain must be invisible.”

The lyrics allude to some police having testified they thought Ms Dhu was faking illness and was coming down from drugs. Medical staff also thought she was exaggerating.

The bigger question is – why did police and hospital personnel decide ‘she was faking it’?

This assumption cost Ms Dhu her life. It denied her a proper health assessment and the care she needed.

Racism mires this nation, despite the denials of the many who reduce the debate to a minimum. Unsurprisingly, our state and federal governments remain idly quiet, as their parliaments do not reflect the demography of the nation in their make-up.

I endured racism as a child and have been haunted by it ever since. I have dedicated much of my research to unveiling it, but only so that we journey forward. I am exhausted by White Privilege talking down to minorities as if racism didn’t exist, as if White Privilege could ever understand what it is like to experience racism.

When Western Australian Coroner Ros Fogliani delivered her findings on Ms Dhu’s death on December 16, no one expected any damning condemnation from the coronial inquest.

We have been burnt so many times, hope was non-existent.

When 16-year-old John Pat died in 1983 in Roebourne, after being bashed to death by an inebriated police officer, Roebourne became to Western Australia what Birmingham had been to Alabama two decades prior: five police officers, who with furious fists laid into Yindjibarndi youth, were acquitted by an all-white jury.

A little over two decades later, we would be let down again when Mulrunji Doomadgee was critically injured in police custody. These police officers are still ‘serving the public’. So too are the police officers and health personnel who were ‘caring’ for Ms Dhu at the time of her death.

In November 2015 and March 2016, I attended most of the coronial inquest hearings into Ms Dhu’s death. I saw the footage, and though it broke the heart to see it, I was not surprised. Much injustice is perpetrated when racism, classism and sexism take hold.

Health personnel and police officers pleaded their innocence during the coronial inquest.

Felix and Marilya capture it best in the song:

“It wasn’t me, wasn’t me, I’m innocent, say the ones who betrayed her in every sense… Now they’re white washing away evidence, will we ever see a cop locked up for negligence?”

During the coronial inquest, I listened to ludicrous assertions, such as, ‘there is no racism or discriminating in the work places of hospitals and police stations’.

All anti-discrimination, anti-racism and cross cultural training teaches us to recognise that every workplace is tainted by racism and discrimination, and only by recognising this can we manage and reduce incidences of racism and discrimination.

Last November, I met with Coroner Fogliani to discuss some of my work in suicide. I also took the opportunity to discuss briefly Ms Dhu’s death and urged for the Custody Notification Service to be recommended.

This service would have mandatorily provided a stout advocate for Ms Dhu, which could have saved her life. I found Coroner Fogliani to be an open-minded individual, and I held out hope that she would come good in the findings and recommendations, despite the weight of pessimism rightfully felt by others.

Coroner Fogliani made eleven recommendations, the majority of which were much needed and long overdue.

She described the maltreatment by police as “unprofessional”, “inhumane and cruel”. However, she did not mention racism.

I would’ve gone further to describe the police’s treatment of Miss Dhu as brutal, malicious and racist. Yes, there was domestic violence incident, and yes, there was a staphylococcus infection and septicaemia. But what ensured Ms Dhu’s death was the police locking her up for fine defaulting, despite the fact that they had been called out to a domestic incident.

The police should have focused on Ms Dhu’s wellbeing, which was their duty of care, not her fines.

The Western Australian Police Commission has a lot to answer for, but has limited itself to reprimands. Country Health (WACHS) issued a statement in December accepting “the comments and recommendations made by the Coroner about the care Ms Dhu”.

The response reads: “WACHS has received, and is currently reviewing, the full Coroner’s report, and is seeking additional advice as to whether any further actions are reasonably required by WACHS”.

The coroner’s eleven findings, which include the call for the Custody Notification Service, were appropriate; however, they fell short of making involved police and health professionals accountable before the criminal justice system for their conduct. The coroner didn’t call out the role racism played, or required compensation for the Dhu family.

As the song illustrates:

Ms Dhu pleaded for her life.

“I am in so much pain.”

“Oh God, someone please help me.”

They did not. Where to from here?

Few Indigenous inmates have finished year 12, prison reform expert says

Gerry Georgatos calls for the same level of education for inmates in prison as is available on the outside.

Almost no Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners have completed year 12, a leading researcher has said, calling for an overhaul of education inside correctional facilities.

The Northern Territory has launched an Aboriginal justice unit, tasked with leading “a total cultural shift” within the NT justice system and creating a formal justice agreement with Indigenous communities.

Gerry Georgatos, a restorative justice and prison reform expert, told Guardian Australia reform was “on the horizon” but governments needed to commit to providing the same level of education for inmates as was available on the outside.

The Don Dale youth detention centre in Darwin. The rates of high-school completion are low among all Australian prisoners, but are even lower among Indigenous people. Photograph: Jonny Weeks for the Guardian.

The rates of high-school completion are low among all Australian prisoners, but are even lower among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – who are already vastly overrepresented in jails. Georgatos, who works closely with prisoners across Australian facilities, said in his experience close to 100% of Indigenous inmates had not finished year 12.

“I visited one Perth-based prison in WA and spoke to 15 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners who were nearing release in the next four to 12 weeks,” Georgatos said. “All 15 had not completed year 12, and half had not been to high school. Half a dozen had significant literacy issues.”

A 2015 study by the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare found only 38% of prison entrants surveyed had attained year 11 or 12. Just 20% of Indigenous entrants had completed the same level of education, and Indigenous dischargees – outside of New South Wales – were more than twice as likely as non-Indigenous counterparts to have only reached year 8 or below.

Studies have linked education with reduced rates of recidivism, a social return Georgatos suggested, alongside increased post-release employment, would offset the cost of increased educational programs.

“The way forward is to get people as many qualifications as they possibly can, and that starts with completing primary school and completing high school if they’re in juvenile detention,” said Georgatos.

Georgatos said his concerns applied equally to juvenile and adult incarceration, and the systems needed a “radical” overhaul.

“Conversations and policy making at the government level are substantive, but they need to be much more substantive. It must be the equivalent to what’s on the outside.”

Earlier this year the royal commission into the protection and detention of children heard from teachers and managers at Northern Territory juvenile detention centre schools.

All noted that the transitional nature of the detention population made determining and providing individual lesson plans difficult, and the large proportion of children who were on remand also made it “an uncertain time”.

“We don’t know whether they’re fit for school or if they’re able to function properly in the classroom. We don’t know their literacy or numeracy academic levels so we need to assess them as soon as possible,” said David Glyde, a teacher at Alice Springs detention centre.

Georgatos said that didn’t matter. “In that window of time while they’re in juvenile detention, no matter how short or long, what’s on offer on the outside should be on the inside,” he said. “That way we have a minimisation of disruption to educational content.”

Georgatos’s call for educational investment coincided with territory’s official launch of an Aboriginal justice unit within the Attorney General’s Department.

The six-member unit is tasked with spending the next year consulting on incarceration and other justice issues with Indigenous groups and communities in order to create an Aboriginal justice agreement.

More than 85% of the NT’s prison population identify as Indigenous.

The NT attorney general, Natasha Fyles, promised the unit would look at “practical solutions” and empower communities as part of the government’s pledge to return decision-making powers to Indigenous people.

“We would like to see a justice system that acknowledges Aboriginal Territorians, acknowledges culture, acknowledges language, and provides for that in delivering a fair equitable justice system for all Territorians.”

Fyles said the unit would examine in-depth, long-term measures, including what was offered within correctional facilities, alternatives to prison, and support for people on remand.

Asked about calls to scrap mandatory sentencing, Fyles said it would be “looked at” by the government.

The director of the unit, Leanne Liddle, said its establishment showed “a total shift of culture of the government”.

She said reducing recidivism and incarceration rates were just part of the unit’s goals.

“We want to embrace Aboriginal people’s leadership styles, we want to make sure that Aboriginal people are heard, that there is local decision-making, and embed that all within a culturally competent framework in the justice agreement.”

She said Indigenous leadership in communities was strong and “they want this change to happen”.

“They want safer communities.”

She said it couldn’t be looked at as a justice issue alone, and the unit would work across departments, including health and housing.

Sam Bowden, a spokeswoman for the Making Justice Work campaign, welcomed the announcement, which responded to one of the organisation’s six pre-election “asks”.

Bowden said the challenge for the government would be to back it up with thorough consultations “and by creating a culture … where conversations about how the justice system and Aboriginal people interact can happen.”

Indigenous prisoner numbers to jump

By 2025 one in two Australian prisoners will be Aboriginal unless generational disadvantage is addressed now, a prison reform expert warns.

Indigenous Australians currently make up about a quarter of the national prison population despite comprising only three per cent of the total population.

Researcher Gerry Georgatos estimates that within eight years, two out of three prisoners in Western Australia will be indigenous, and in the Northern Territory it will edge near the 100 per cent mark.

On Monday the ABC revealed Darwin’s adult jail population – 84 per cent of which are Aboriginal – reached a record high in April.

“If governments fail to invest to transform the lives of prisoners and former inmates, (more) prisons will be built,” Mr Georgatos said.

Mr Georgatos says while education is the key to breaking the cycle of crime, very few indigenous inmates have completed Year 12, and he wants to overhaul schooling inside correctional facilities.

Not only would inmates gain qualifications with increased educational programs, but they will also be psycho-socially validated and strengthened, which in turn reduces trauma, he said.

Without action, Mr Georgatos predicts Aboriginal suicide and incarceration rates – already among the highest in the world – will worsen.

“The nation should weep, but more importantly should act, when 80 per cent of suicides of children aged 12 years and (under are Aboriginal),” he said.

The suicide prevention advocate said nearly 40 per cent of indigenous people remain trapped below the poverty line, leaving them highly vulnerable to aberrant behaviour.

“Prisons are filled with the low-level offending borne of the tsunami of poverty-related issues,” he said.

“If we do not respond to the elevated risk groups then we are discriminating, we are leaving them behind to rot.”

https://nz.news.yahoo.com/indigenous-prisoner-numbers-jump-054559836–spt.html