FACE OF WE DON’T CARE

Teenager’s watershed interview exposing a BROKEN SYSTEM that saw her live in 76 ‘homes’ in 12 years — including once with a CHILD PREDATOR which led to a SUICIDE ATTEMPT

Annabel Hennessy, The West Australian newspaper, December 16, 2019

Annabel Hennessy, The West Australian newspaper, December 16, 2019

A teenager who tried to take her own life after enduring 76 different out-of-home care placements in 12 years while under the protection of the WA government has detailed her shocking tale of neglect. Sixteen-year-old TahShae today reveals how she was homeless and lived in the same apartment as a now convicted predator while in State care.

The West Australian received special permission to identify Tah-Shae in what is believed to be one of the first times a ward of the State has been allowed to be named and pictured in a news story. Tah-Shae is speaking out to expose a system she says is failing the kids it is meant to protect.

Tah-Shae was the child who wanted to die.

And lying still on the parched summer grass of an oval in Perth’s northern suburbs the girl who had just turned 14 almost did.

It was primary school students who saw her motionless body and ran for help.

Kids almost the same age as Tah-Shae had saved a stranger, stumbling on a scene they were too young to understand.

She was also too young, but despite her fragile age she had already seen too much.

The memories come back in flashes. Walking alone on a Perth city street at midnight because she was scared to go to the home that wasn’t really home.

Moving house again and again. Being shunted 76 times. From the flat in Bunbury to the group homes in Kalgoorlie.

The unit in Kalgoorlie she can’t forget. The place with the man who taught her that monsters are real.

And then, at 14 when her world should have been filled with school playgrounds and first crushes, being consumed by the feeling she no longer wanted to be here.

76 ‘HOMES’ IN 12 YEARS

Tah-Shae who was taken into care by the WA Department for Child Protection as a baby, has bravely decided to share her story in a bid to shine a light on what she sees as the continuing failures of the system.

In a rare circumstance, The West Australian has been granted permission by the department to identify Tah-Shae as a child in care and show her face. Tah-Shae hopes by going public she can drive change for the thousands of other children in care whose stories remain shrouded in secrecy.

The 16-year-old, who two years after her suicide attempt is happy and stable, also wants to give strength to others with mental health issues.

The facts Tah-Shae speaks so calmly about are stark.

From 18 months old when she was removed from her mother in Kalgoorlie, to age 14, Tah-Shae had 76 different care placements. On average she moved once every two months.

This included group homes, foster carers and kinship placements in Kalgoorlie, Coolgardie, Perth, Esperance, Northam, Mandurah and Bunbury. She was shifted so often she cannot remember many of the placements.

She also experienced homelessness while under department care.

“I didn’t sleep on the streets, I was too scared to sleep on the streets, I stayed out all night and would meet someone new to hang around with,” she said.

“They don’t check up enough, they wouldn’t even know that I was homeless.

THE MONSTER’S BALL

In December 2017, two months after her 14th birthday, TahShae tried to take her own life.

After becoming unconscious she was found by passing school students and rushed to hospital.

“I just ended up snapping . . . I got so depressed. I didn’t really have any friends either so I felt more depressed that I had no one to talk to. I just sat in my room all day, every day, I just decided, I said I’m done,” she said.

It wasn’t her first attempt. From the age of eight, TahShae started to feel engulfed by loneliness. “It got to the point where I kind of knew I wasn’t where I was meant to be and I started questioning where was my real mum and all them sort of things,” she said.

“I had clothes and food, but I didn’t have stability . . . that was the hardest thing. I’d be a different person, if I grew up with stability.”

When Tah-Shae talks about her experiences in care she emphasises that she was, and legally still is, the department’s child. They had a responsibility for her welfare.

But Tah-Shae says when she was about 12 she found her own accommodation and ended up living with a man in his 40s in Kalgoorlie.

“They got to the point where they said they didn’t have any more placements for me. So I went and stayed with a friend, well so-called friend, of a family member,” Tah-Shae said.

“The department knew where I was staying, they came and checked up on me and I gave them all the details of this person I was staying with. I told them his name and that I was going to school.

“They should have done a criminal check on that person and checked if that person was suitable for me to stay with. They didn’t do that and that’s how they failed me.”

Tah-Shae says he sexually assaulted her.

Tah-Shae made a complaint about the abuse to police in 2016, but decided not to pursue it after receiving threats from people who knew him.

The man, who is now 45, was convicted this year on separate charges for sexually assaulting a 12-year-old, unlawful detainment after he locked a 31-year-old woman in a car against her will for 12 hours and reckless driving.

Court transcripts state he is an alcoholic who had a previous conviction for breaching a violence restraining order in 2010. Tah-Shae asked for details of the assault to be included in this story because she sees it as the department’s biggest failure.

“I do want that out there,” she said. “The whole way they failed me was not doing a criminal check and by that I got sexually assaulted . . . that affected my mental health and nothing is going to fix that.”

MINISTER’S CONCERN

A Communities spokesperson said Tah-Shae had moved “a significant number of times over several years”.

“The reasons for these movements are complex and we made every effort to provide a safe and stable environment for Tah-Shae,” they said.

They said Tah-Shae had chosen “to spend time in the care of unendorsed carers for a very small portion of the time she was in Communities care”.

“These circumstances were not arranged by the case worker or team supporting Tah-Shae but in some circumstances, later in the piece, the department was able to assess and turn these temporary arrangements into placements for Tah-Shae,” they said.

“The department did not approve the placement that led to Tah-Shae’s allegations of assault.”

“We are committed to ensuring that no child or young person in care is ever left to make their own accommodation arrangements.

“We have a range of care options, including emergency carers and also contracts with community sector organisations to provide placements.”

The spokesperson said the department had supported Tah-Shae in telling her story because it was “committed to listening to children in care and hearing their voice.”

Tah-Shae said she should

have never been allowed to choose her own placements at such a young age.

“I don’t think the department should be letting a child under the age of 16 years old make the decision themselves. They are responsible for that child,” she said.

Minister for Child Protection Simone McGurk said she was concerned about the many placements. “Seventy-six is a large number of placements, and it does concern me,” she said. “This case is a very complex one and, fortunately, that number of placements is not the norm.”

She said there would always be a placement for a child in State care. “However, the department advises me there could be circumstances where the child does not accept that placement,” she said.

“There are some instances where young people in care vote with their feet and will leave the placement the department has arranged for them. Sometimes where they choose to live may be deemed unsuitable and not approved by the department.

“The department works to ensure that these young people are in a safe environment. In the case of Tah-Shae these efforts were evidently not successful.”

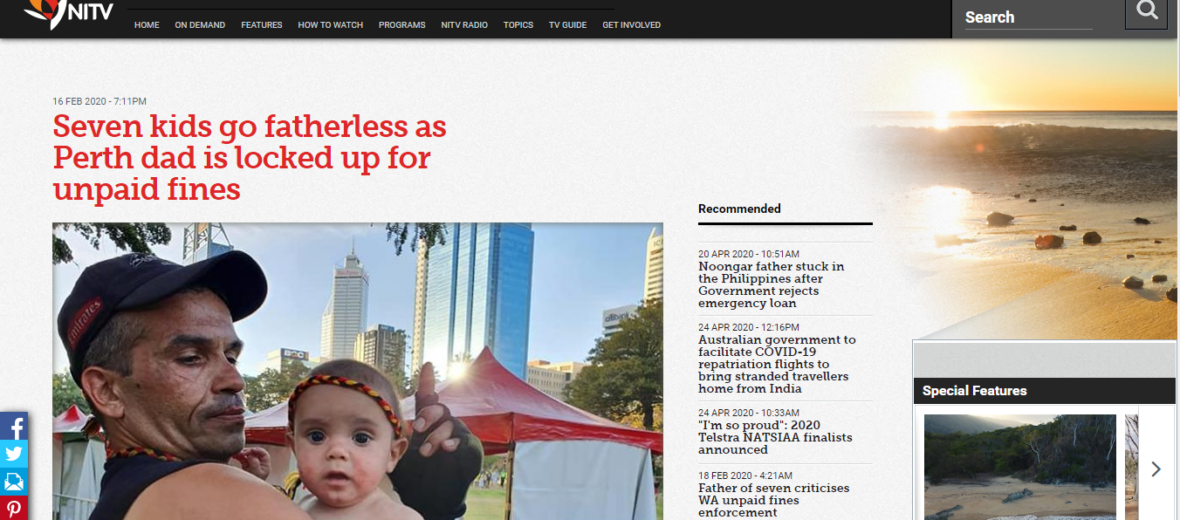

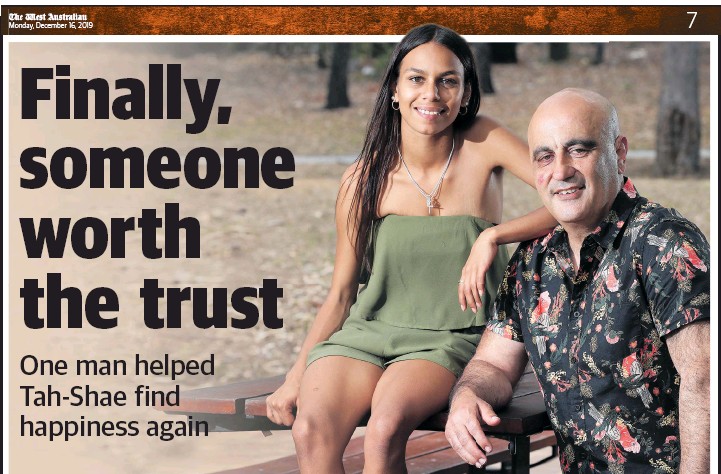

FINALLY, A SAFE PLACE

In 2017, on the day of her suicide attempt, Tah-Shae met mental health activist Gerry Georgatos. This, she says, was the start of her new life.

Mr Georgatos, who runs the National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project, helped Tah-Shae reunite with her biological mother who was living in Brisbane with her two youngest children.

With support from Mr Georgatos, Tah-Shae moved to Queensland to live with her mother. From when she had been taken into care at 18 months old, Tah-Shae had only seen her a handful of times.

“As I grew up, I always wished for that. All my friends, they had their mum and their dad and that’s what I’d always wished for,” she said. “Finally I had my mum there and it just felt good. It felt like I was back together again.”

In Brisbane, Tah-Shae has found happiness. She is going to TAFE, has supportive friends, a boyfriend and a beloved pet staffy. The teenager is also a dedicated older sister to her two younger siblings, aged three and eight.

“I’ve never had this. I finally feel like I’ve got people that care. I’m stable. It’s all I’ve ever wanted,” she said.

Tah-Shae’s mum, who asked not to be named, said while their reunion “had healed a lot of holes in her heart” she could not stop thinking about what her daughter had been through.

Tah-Shae says she understands why the department removed her from her family, after concerns for her welfare, but feels more should have been done to reunite them.

“Looking at the reports at why I’m in care, they did a good thing (in the initial removal) . . . but they should have done more (to reunite us)” she said.

“Mum has a little boy who is eight years old and has been in her care since he was born. I just didn’t understand why he was allowed to be in her care and I wasn’t.”

Tah-Shae, who is Aboriginal, also feels disconnected from her culture as a result of her time in care. “I don’t really know much of my culture. I only know the name of my culture,” she said.

“Wongi on my mum’s side and then Noongar Yamaji on my dad’s side.”

HOW TO SAVE A LIFE

Tah-Shae credits Mr Georgatos with saving her life.

In Brisbane he has connected her with a local social worker who works with her on a volunteer basis separate to the department.

“It’s been hard, I tried to commit suicide, felt alone, depressed, felt like no one cared, but then Gerry and (the social worker) came into my lives and changed really everything,” she said. “I got better. The more I talked about it and got out of like the whole of that situation with Perth and Kalgoorlie the easier it became.

“And I feel like a better person

They should have checked if that person was suitable for me to stay with. They failed me. 16-year-old Tah-Shae

now and I haven’t attempted it since.”

Tah-Shae has graduated year 10 of school in Brisbane and is six months away from completing Certificate II at TAFE in hairdressing. Now she wants to find a course that will put her on the path to becoming a lawyer.

“I’d like to change some of the ways the system works,” she said. “Kids need stability. Every child needs stability, discipline, you know, people that stay around all the time, not fresh faces.”

Mr Georgatos, pictured, says the support he has given her should have been provided by the department years ago.

The key to it was simply consistency and showing her she was loved and believed in

“Tah-Shae has made incredible transformation. She puts it down to myself and others, but it’s actually down to her. She always had the will, she’s an intelligent, articulate, young individual who just needed the opportunity to be supported,” Mr Georgatos said.

He has flown to Brisbane eight times to visit Tah-Shae since 2017. Last year, for her 15th birthday he organised a holiday for her in Cairns. He wanted to show her life could be beautiful.

“I loved the beach walks, it was amazing,” Tah-Shae said.

Mr Georgatos said he hoped Tah-Shae’s story would spark change.

“I was beyond shocked when DCP informed me this young child had 76 placements in 12 years. On average, six placements each year. That alone should launch a public inquiry,” he said.

THEY NEVER CALL

Despite now living in Brisbane, Tah-Shae is still under legal care of the WA State.

While she gets money for weekly groceries, there are few check ins. When she approached the department for permission to be named in this story, she was told she no longer had a caseworker.

“They never really checked up on me. Even with this whole big change, me being over here in Queensland, they only came and had a visit once,” she said.

“They don’t call me. I’ve actually got to call them.”

A department spokesperson said interstate placements were complex. “Whilst interstate protocols exist to enable government departments in other States and Territories to provide support locally, this is often difficult to arrange and monitor from a distance,” they said.

“The full range of the department’s support is available to any child in care . . . regardless of whether they have an allocated caseworker.”

Around Tah-Shae’s neck hangs a silver “16” pendant that was a gift from her boyfriend’s mother.

It’s the birthday she didn’t think she’d reach, but also a reminder that she has love in her life. She also wears a crucifix.

Despite everything, she still believes in God. For other children in care feeling lost, her message is simple: keep fighting.

“I haven’t really heard any story from a child in care actually talk about their experience in care,” she said.

“That was another reason I wanted to do it (the interview). To put it out there that it’s OK to talk about your problems being in the department.”

“For people that are going through some of the same things know that if you stay strong, you’ll get through.”

If you need to talk to someone, call Lifeline on 13 11 44

Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800

If you are interested in becoming a foster carer, call 1800 182 178

Harmony’s story: Breaking the cycle of youth incarceration in Western Australia

After eight weeks, Harmony completed a Certificate 3 in Civil Construction. Source: Aaron Fernandes, SBS News

For the first time, a new program in Western Australia is following the journeys of young people out of juvenile detention.

By Aaron Fernandes, SBS NEWS, 5.7.2020

The statistical odds were all working against Harmony.

When an Indigenous person ends up in juvenile detention in Western Australia, they are more likely to end up in an adult prison later in life.

Three months ago, Harmony sat in a cell at Banksia Hill Detention Centre in Perth’s southern suburbs, the only prison in the state for juvenile offenders.

Currently, there are 108 detainees at Banksia Hill, the youngest just 11 years old. Seventy-eight of them are Indigenous.

“My life is s***, that’s why I ended up in Banksia,” Harmony, now 18 years old, tells SBS News.

“Just the freedom and not being able to see family (bothered me). I did seven months, got out for a month, then went back for another six. I just got out again.”

Her prospects for turning her life around became even bleaker in February this year, when eight major not-for-profit organisations stopped going into Banksia Hill to work with young offenders, due to coronavirus concerns.

Banksia Hill is the only facility in WA for juvenile offenders. Aaron Fernandes, SBS News

The WA Department of Corrective Services looked for new service providers to fill the space.

“There are a lot of issues around adolescent mental health and [a] very high number of Aboriginal people [in Banksia Hill],” WA Corrective Services Commissioner Tony Hassall says.

“What we wanted to do was make sure we covered all those issues, of suicide, self-harm and trauma. Something that would be unique and different in terms of managing young Aboriginal girls in the system”.

The NSPTRP received a small grant to work in Banksia Hill.Aaron Fernandes, SBS News

Corrective Services partnered with the National Suicide Prevention & Trauma Recovery Project, a Perth-based organisation proposing an intensive support program for Indigenous girls.

The aim of the program was to build trust with the girls while they were at the facility, then follow their journeys post-release, to ensure risk factors such as housing, mental health and access to education and employment were mitigated.

“We supported them with a daily presence, assertive outreach while they’re in prison and constant support from the first day they’re released to prevent any risk of re-offending,” NSPTRP National Coordinator Gerry Georgatos says.

“We didn’t cherry pick which kids we worked with, we took the toughest ones with the hardest circumstances”.

Children are sent to Banksia Hill from all over the state, with many there awaiting their first court appearance or because they’ve been denied bail.

The NSPTRP program targeted around a dozen Indigenous girls with a history of serious offending, including violent assaults, car theft and high-speed chases.

Many are themselves victims of abuse and subsequent trauma, from homes where poverty, violence and substance abuse are pervasive.

“If it was your son or daughter (incarcerated), you would want them to have every possible chance of leaving prison and not going back,” NSPTRP Director Megan Krakouer says.

“We know a lot of the families that these kids come from, we work with them too because intergenerational poverty is a factor in most of these stories.”

Harmony is now qualified to work on a range of worksites. Aaron Fernandes, SBS News

It was during the first visit by NSPTRP to Banksia Hill in March this year that Harmony reached out for help.

“They came into Banksia … I just walked up to them and asked if I could get some help. Try to get back on track, try and get my life sorted out,” she says.

At that point, Harmony had only a few weeks left until release, but had no job, no education and no stable housing.

“I’m 18, I dropped out (of school) in year eight, at the start of year eight,” she says.

Harmony received daily visits from the NSPTRP prior to her release from Banksia Hill.

“(Harmony) was about to come out of Banksia with her juvenile detention photo ID, and that’s it,” Mr Georgatos says.

“She didn’t have the basic documentation, in order to apply to get a drivers licence, a healthcare card or enrol in training for employment, or access Centrelink.

“So the first thing we had to do was organise documents to get her ID to get her to that 100 point checklist.”

Harmony completed her course in eight weeks. Aaron Fernandes, SBS News

Driving Harmony to appointments, the NSPTRP followed her through the process of enrolling, delivered food to her family home and conducted around-the-clock support.

“We drove her to appointments, bringing her to training everyday when she needed to be here. Basically, be there for them the entire way,” Ms Krakouer says.

“This type of work doesn’t finish at 5pm, you have to be reachable at all hours, whether it’s via Facebook, messages. Just keeping it real.

“This kid is a bright kid, she’s a lovely person. And sometimes all you need to show is that there’s love around them and circumstances can change.”

Harmony then enrolled in a Certificate 3 in Civil Construction, provided free of charge by a workplace training centre with experience working with ex-prisoners.

“We’ve had hundreds of success stories come through here … guys out of incarceration that are making good money now. Harmony is the first of the younger ones, they’re the ones we should be helping”, Skills Training and Engineering Services General Manager Clinton Kieswetter says.

Even with support, it took multiple attempts for Harmony to achieve her qualification. The risk of failure however meant an almost certain relapse into criminal behaviour and adult prisons.

“I never thought I’d be able to do it, but once I started doing it, I seen that it wasn’t as hard. I gave up a few times, but I’m finished now,” she says.

“If I could do it, anyone can do it. So just give it a go.”

The program is being considered for further funding. Aaron Fernandes, SBS News

Mr Georgatos is quick to point out that Harmony’s journey is far from over. The next step is to find her independent housing and then a permanent job.

Even then, nothing is guaranteed.

“We work with them, even if they’re cursing us away. We work with them, even if they don’t want that support any further,” he says.

“We keep on engaging with them until we translate that engagement into outcomes. Into meaningful activity, into education, into training and employment,” he says.

“(It’s) everything that they want, but obviously they have had hardships that need to be unpacked, trauma that needs to be unpacked. We believe in them relentlessly until they start believing in themselves.”

The NSPTRP is now being considered for future funding by WA Department of Corrective Services.

The course was provided for free by STES in Bibra Lake. Aaron Fernandes, SBS News

“This (program) is unique in terms of its intensity, intensive support for young girls who were vulnerable and at risk,” Commissioner Hassall says.

“They’ve taken a young girl from being in Banksia Hill right the way through the journey. That sort of end-to-end approach, we actually haven’t had before”.

Mr Hassall says the success of the program continues a recent push across government agencies in Western Australia to promote partnership, culture and participation when working with Indigenous communities.

In WA’s Kimberley region, the department has launched a juvenile justice strategy, co-designing youth services with local communities.

“There is a push across government to be aligned in how we manage these challenges. We’re all agreed on the objectives … reducing the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people in the justice system,” Mr Hassall says.

“(The NSPTRP) is different is terms of, they follow the person all the way through. They start that intensive work in the centre, and we’ve had to do things differently, we’ve had to operate in a slightly different way, and that’s fine.

“That then drives in us a slightly different appetite in how we take risks and how we manage risks”.